The January full moon, which eclipsed fully, was astonishingly beautiful. I captured these photos soon after its rise, while ships were passing in the channel and the dusky horizon was brushed in pastels.

The January full moon, which eclipsed fully, was astonishingly beautiful. I captured these photos soon after its rise, while ships were passing in the channel and the dusky horizon was brushed in pastels.

I hope to always place principles above political partisanship. Though they don’t do so nearly as often as I would wish, when political leftists take stands that align with my loyalty to civil liberties, I will champion them. So today I stand with residents of two very left-wing places – Boulder, CO and the state of New Jersey. They are defying recent laws that drastically cripple their Second Amendment rights: an “assault weapons” law in Boulder and a magazine capacity restriction in NJ.

Early reports suggest that very few people are complying with the new laws. The requirements to surrender or destroy previously legal property are being ignored en masse. I am not greatly surprised. Though advocates of firearm restrictions are prominent within the Democrat party, I have long suspected – and hoped – that only a minority of Democrat voters outside of large urban areas would actually tolerate such restrictions being imposed upon them.

Gun owners in Boulder and New Jersey are not turning in their weapons or magazines. Regardless of their political leanings, I applaud them for their courage. When in defense of liberty, civil disobedience is right and noble.

Details from Boulder (quoted from the Washington Times):

Boulder’s newly enacted “assault weapons” ban is meeting with stiff resistance from its “gun-toting hippies,” staunch liberals who also happen to be devoted firearms owners.

Only 342 “assault weapons,” or semiautomatic rifles, were certified by Boulder police before the Dec. 31 deadline, meaning there could be thousands of residents in the scenic university town of 107,000 in violation of the sweeping gun-control ordinance.

“I would say the majority of people I’ve talked to just aren’t complying because most people see this as a registry,” said Lesley Hollywood, executive director of the Colorado Second Amendment group Rally for Our Rights. “Boulder actually has a very strong firearms community.”

The ordinance, approved by the city council unanimously, banned the possession and sale of “assault weapons,” defined as semiautomatic rifles with a pistol grip, folding stock, or ability to accept a detachable magazine. Semiautomatic pistols and shotguns are also included.

Current owners were given until the end of the year to choose one of two options: Get rid of their semiautomatics by moving them out of town, disabling them, or turning them over to police — or apply for a certificate with the Boulder Police Department, a process that includes a firearm inspection, background check and $20 fee.

Judging by the numbers, however, most Boulder firearms owners have chosen to do none of the above, albeit quietly.

“The firearms community in Boulder — they may be Democrats but they love their firearms,” said Ms. Hollywood, herself a former Boulder resident.

And from New Jersey (quoted from Reason):

Thanks to a December 5 ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit, New Jersey’s ban on gun magazines that hold more than 10 rounds took effect on December 10. By that date, all owners of heretofore legal “large capacity magazines” (LCMs) were required to surrender them to police, render them inoperable, modify them so they cannot hold more than 10 rounds, or sell them to authorized owners. Those who failed to do so are guilty of a fourth-degree felony, punishable by a maximum fine of $10,000 and up to 18 months in prison.

How many of New Jersey’s 1 million or so gun owners have complied with the ban by turning LCMs in to law enforcement agencies? Approximately zero, judging from an investigation by Ammoland writer John Crump. Crump, an NRA instructor and gun rights activist, “reached out to several local police departments in New Jersey” and found that “none had a single report of magazines turned over.” He also contacted the New Jersey State Police, which has not officially responded to his inquiry. But “two sources from within the State Police,” speaking on condition of anonymity, said “they both do not know of any magazines turned over to their agency and doubted that any were turned in.”

Home is the sailor, home from the sea, and home is my Gummy Bear, free from her bondage. Nine days after her second major surgery, Gummy’s sutures were removed today; she is no longer bound by kennel and collar.

My happiness is equaled only by that of her brother, Ulysses, who has not left her side all evening. He is curled up next to her now.

Gummy underwent a subtotal colectomy; 80% of her colon was removed, in hopes of easing the symptoms of megacolon that developed a year after her last surgery, which left her unable to control her bowel movements and which often left her miserably constipated. The incision is quite impressive, running from just below her rib cage to her lower abdomen.

Throughout the ordeal – hours of driving, the procedure itself, eight days wearing a collar while confined in a dog kennel, multiple medications three times a day, and manual urinary expression – she maintained her sweet, cheerful disposition and never held a grudge against me.

Most touching of all was brother Ulysses’s tenderness with her. As he did following her first surgery more than two years ago, he refused to leave her once she returned home. Though he is my most active and energetic cat, he chose to confine himself in her kennel rather than be apart from her. He would not come out for more than a day.

Gummy now lacks her tail and most of her teeth and colon; she cannot go to the bathroom without my help; she must take oral medication every day. Yet she flourishes. This most gentle and sweet little calico cat brings joy to me and the other cats. Long may she live and inspire.

Now may the new year begin. As is the tradition through much of the south – and adhered to intensely within my family – I’ve prepared black-eye peas, corned beef and cabbage, and jalapeno cornbread (the Texas version). I wish the house smelled this warm and delicious all year round, but on this one day I accomplish about a quarter of all the cooking I’ll get done for the rest of the year.

Now to share with neighbors. Blessings on you all through the year to come!

Now into the 8,760th – and final – hour of 2018, I find myself bewilderingly content. The house is warm and soft, lit only by Christmas lights; Vivaldi’s “Gloria” plays on the stereo; I’m sipping a fine 16-year-old Scotch; the bay is glassy still under a windless sky; my oldest girl cat, Jenny, sleeps in my lap (I press my face into her coat and am calmed by her soft roar), while her seven adopted brothers and sisters doze nearby – their peace comforts me.

I’ve spent much of the evening preparing the New Year feast – sorting black-eye peas, dicing cabbage and corned beef, mixing cornbread ingredients – and finishing the eccentric tasks that I perform each year-end. Most of all, my thoughts scan back over the year, searching for moments when I spoke and behaved honorably and kindly. I remember a few such moments, and from them I take hope.

But many more are the moments when I spoke angrily without cause, or acted peevishly with little reason. When, despite comforts and blessings far beyond anything I have deserved, I was ornery and thoughtless; when I could have spoken a kind word but did not; when I could have thought of others before myself, but did not; when a cold midwinter wind chilled my spirit.

Regrets wash over me like a long summer shower. And I am glad for each of them. I reject the pop-psychology proposal of having no regrets. Regrets straighten us; if we attend to them, we may yet be better.

And that is all I hope for the year that just this minute began: that I am better. That come this night a year from now, I will scan the closing year and find that I was, in the balance, a bit more kind and thoughtful – a far cry from all I should be, but nearer than before.

Blessings on you, my friends, in the year ahead.

Yosemite stole my heart many years ago – I’ve climbed its mountains and hiked at least a hundred miles of its trails – and the central coast enchants me, but when it comes to personal liberties – the political and social quality I cherish above all others – I am most at home in Texas and the freedom states of the west (Arizona, Utah, Wyoming, Montana). To live anywhere where those liberties are constrained, would chafe me too severely to be happy.

A fine example: while browsing at for a fishing shirt at Marburger’s, Old Seabrook’s sweet little sporting goods store, I came across a Springfield XD-9 on sale. I’ve been resisting the urge to replace my too-small carry pistol, a Ruger LC9, with something with a longer barrel and double-stack magazine (the LC9 is only a 7-round single-stack). My budget didn’t call for splurging for another gun, but the price was right; the Marburger folks greeted me as a homeboy they know well; and I am a strong advocate for supporting local, independent businesses.

A CHL and background check later, I walked out of there with a lovely new pistol. On the case was this tag: “Not Legal In California and W/High Capacity Magazine.” Thank God for Texas – and in your eye, California!

Light and comfortable on the hip:

One cannot live on this bay for 23 years, with eyes open, and not feel awed by the unrestrained flourish and fecundity of birds. In my small world, they furnish the motion and sound that dominate each day. In other words…life.

I have made a hobby of knowing them. I watch them, study them, listen to them. A shelf in my house holds nothing but books about birds, all well used. I know our birds by sight, by silhouette, by flight pattern, by time and place, by behavior, by song. I know our residents, and I know those who only visit or migrate here to spend winters. I treasure each species, each bird, and each time I learn something new about them I treasure them more. In my relations with birds, familiarity breeds affection, and I know and love them well.

But they can still humble me. Just tonight, as I stepped out to the deck to sip a bit of Scotch and to watch lightning far to the east, I heard a bird I have not heard before. A single, clear, brief note, falling and echoing faintly at its end, sounded above the shore. It continued again and again, so that I could hear the bird rising in the air over the bay, then dropping and moving over my yard before soaring again over the water.

I was entranced. This was a bird call like no other I’ve heard before. The night is very dark, no moon lightening a sky shrouded by storm clouds. I got no glimpse of the bird itself.

What was it? I have no idea. Perhaps I never will. I haven’t heard it before in all these years; perhaps I’ll never hear it again. It will trouble and perplex me – I really want to know this new bird that courses through my world so late at night.

I’ll have to live instead with an intriguing mystery.

In November, 2000, a month after moving here, I planted two Canary Island date palms in the bare space between the house and the bay. Less than two feet tall at the time, they had grown from seeds I collected from the best trees I could find. I selected these two from a few dozen I tended in pots in the garage. They were to be the tropical showcase of the bay-front yard.

I took great care with them, and they flourished. They grow slowly, as is their nature, but within a few years they were displaying all the traits I admire in the Canary: sturdy trunks; long arcing leaves; a broad canopy unequaled among palms. They shaded my cats and me through summer afternoons, and sheltered birds innumerable, especially the flocks of monk parakeets that seem born to pair with such a tree.

Over these 18 years they have endured the extremes of weather the Texas coast is known for: fierce storms, heat and drought, even the rare freeze and ice. Returning after hurricane Ike in 2008 I found my house and all that I owned wiped from the face of the earth, but the date palms stood; though a bit worse for wear, they survived that storm’s 17-foot storm surge and 110 mile-per-hour winds. Through storms and calm, I marveled at how they can be both durable and delicate.

But they won’t survive a bacteria so rudimentary that it has no cell wall and cannot be cultured. The Texas Phoenix Palm Decline phytoplasma, tiny as it is, will do what even the ferocity of Ike could not do: kill my old friends.

The largest is dead now. As is typical with TPPD, its lowest leaves browned and died; those above soon followed. Nothing green remains on it now, only a handful of dead leaves I haven’t yet removed. The other palm still displays a crown of new green leaves, but its lower leaves are browning and dying, showing the certain early stages that will take the tree before summer is gone.

It breaks my heart to see them now. Yes, they are only trees. But their roots were put down here when mine were. Their tropical grace has framed my view of the bay through changing light and seasons, through countless rises of sun and moon, through bay storms and blue skies. They have cheered and soothed me through my own storms and frosts.

I cannot imagine this place without them. When they are gone, they will leave empty places in the landscape, and in my heart.

The largest, now dead

The smaller, showing TPPD symptoms

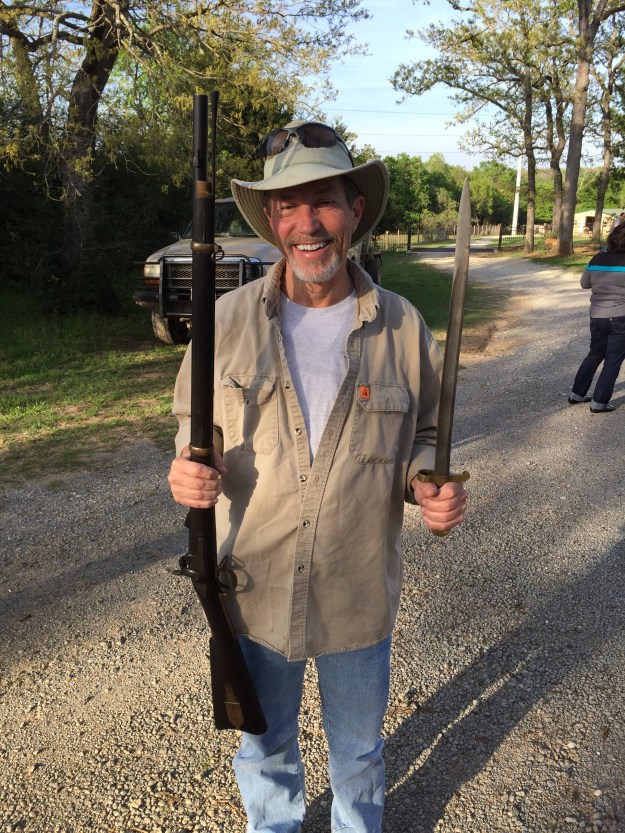

How to explain this: even as I am working through a long series of books about American Indians in the 19th century, the most recent two winnowing down to Custer, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and the iconic battle at the Little Bighorn valley, brother Kevin – unaware of my reading habits – tracks down and buys a rifle which was, in all but the most minor details, the very model used by the Seventh Cavalry on June 25, 1876. The “Allin conversion” or “Trapdoor” model of the Springfield carbine.

Used widely by the Union army during the civil war, many thousands of the rifle were available after the war ended. The government decided to use them, but being muzzle-loading rifles, they were already obsolete; many white settlers and Indian tribes had newer repeating rifles, including the Winchester that held 17 rounds.

Gun designer Erskine S. Allin invented a ‘trapdoor’ device which converted the Springfield into a breech-loader; soldiers could now fire up to 20 rounds per minute instead of two. Kevin’s rifle is from the first conversion, in 1865, and bears the Union mark on the wood stock. As if proof were needed, the muzzle rod is still with the rifle.

By 1873, Springfield was manufacturing carbines that were native breech-loaders, but all other characteristics are identical to the conversion model that Kevin has. I recently had a chance to hold the rifle. It’s weight and utilitarian beauty seemed a palpable confluence of past and present; a connection, small and remote though it may be, with a moment in history still vivid in my mind.

After wandering off for more than a day, my handsome Kitty Carson has returned. Hungry, craving attention and time with his favorite catnip mouse, but healthy and happy. Welcome home, big guy!